1. Start Strong

What I learned about memorable openings from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Whenever we open a book or start a story, what do we look for? People may have different answers to this question. Some might say a strong voice, others immediately look for a hook… or stakes, or tension, or a clear sense of character, or a specific emotional reaction like laughter or fear. All valid answers. But if I collected those responses and bundled them together, the answer would end up becoming: “A reason to read on.”

For us writers, the strength of an opening depends largely on how well we are able to deliver that reason to our readers. And because that reason can take so many forms, what matters to us is knowing what kind of reason will appeal to the readers we want to write to. A voice-driven opening could bore a reader who prefers to know the stakes from the first page on. Likewise, an opening that simmers with tension could feel too abstract to readers who prefer to get to know the characters and their world before the story really begins. Some writers can blend these reasons in a skillful way, delivering openings that feel genuinely unique. But rather than try to make our openings combine as many of these reasons as possible (which could overwhelm our readers), we should be thinking more about who we want our readers to be, and what they’re interested in seeing.

Looking at my own process, I find that an effective approach for building a strong opening (though by no means the only way) is to make sure it has a clear trajectory or direction. As you work out your first draft, start asking yourself the question: where is this going? What should my reader expect to happen in this story? The answers to these questions can appear as early as the title of your story and as late as the end of your first act. Moreover, the trajectory of your story can be subtle, foreshadowing it through a small detail or line of dialogue, or explicit, sometimes even flat-out telling you where the characters will be by the end.

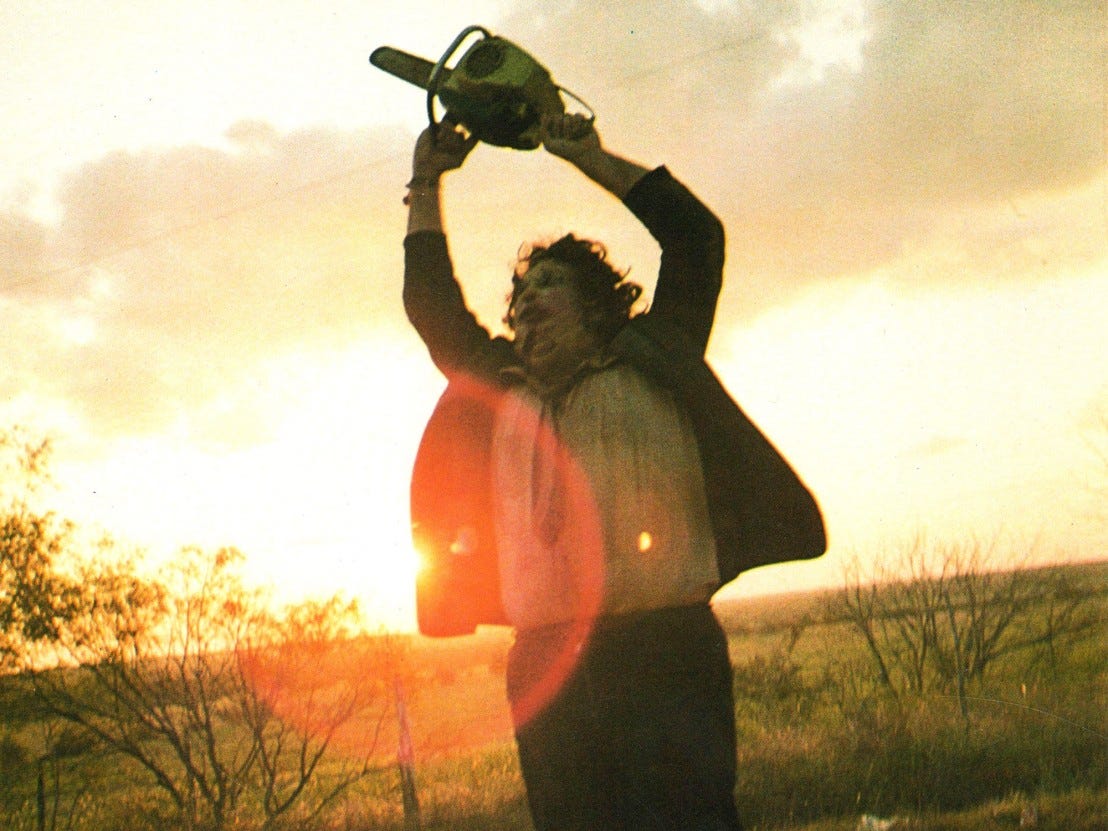

One of the strongest openings to a film I’ve seen in recent memory is that of the first Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). If you haven’t seen it (for understandable reasons! A lot of it was difficult for me to watch without my hands over my face, even as a horror fan), let me tell you how it starts.

The film opens with a block of crawling text, which is also read aloud by a narrator. Here is the full text of that crawl (content warning for ableist language):

The film which you are about to see is an account of the tragedy which befell a group of five youths, in particular Sally Hardesty and her invalid brother, Franklin. It is all the more tragic in that they were young. But, had they lived very, very long lives, they could not have expected nor would they have wished to see as much of the mad and macabre as they were to see that day. For them an idyllic summer afternoon drive became a nightmare. The events of that day were to lead to the discovery of one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

Once that’s done, we see nothing for a long while, hearing what sounds at first like someone digging. Then the camera does a slow montage of shots. Of what isn’t immediately clear—we see what looks like decayed body matter, but we can’t really be sure that what we saw was, in fact, what we saw, not at least until the sequence is done. When the camera opens again on a shot of a desecrated corpse melting in the Texas sun, it turns out that the movie has opened on a grave robbery.

(If you’re feeling brave, here is that whole opening sequence on YouTube.)

Suppose you’re going to the movies and you get the itch to watch something scary. Now showing is a movie whose title is The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Already this title sets up a trajectory for your experience: multiple people are going to be killed, presumably by chainsaw. It’s not a murder, it’s a massacre, so the body count doesn’t stop at one. You go into the movie, take your seat, and the first thing that happens is this opening narration, which specifies the situation presented in the title with a series of pertinent details: there are up to five victims in this story, two of whom are a brother and sister. The fact that they are named among the five suggests that they are central to the story; we’ll have to look out for them once we start meeting the characters. Crucially, it is ambiguous whether they survive this film, because of the phrasing of “had they lived very, very long lives,” which could mean they die during the movie or their lives don’t go on much longer, as a consequence of the massacre. Okay, now we’re ready for the movie to really start. Then we have the grave robbing sequence, and our mind is boggled by the images, which resonate with signal descriptors we got in the narration: “mad”, “macabre”, “nightmare”, and “bizarre.”

I’m not saying this is how people typically absorb an opening, but these are certainly details that embed themselves in the viewer’s subconscious, creating expectations. What is the most mad and macabre thing I could see from a film that has this title? What would strike me as a bizarre nightmare? To take this a step further, it’s often said in horror that what you imagine of the horrifying thing is usually worse than how it actually appears, but in this case, director Tobe Hooper and crew are actually able to give you something that fits this description. How? By taking one thing that’s already quite terrifying and distorting our perspective with too brief, too unnerving glimpses of the thing, thus magnifying our sense of what the thing could be.

Essentially, the film is able to draw its trajectory in a completely straightforward manner, i.e. if not the title, then the opening narration. As I said before, a story certainly doesn’t have to declare its trajectory in such a straightforward way, but it does make the path clear for us by giving us an idea of what we should expect if we read on. If I come to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre to get scared, the movie basically opens with the first of many scary things it can present to me. The challenge it faces as the movie goes on is this: if the opening is that scary, how can it escalate? What could it do next that is even scarier than what I just saw?

To put it simply, trajectory is a set of expectations arranged in a line that stretches unbroken from beginning to end. Telling a story is an act of balancing those expectations, either satisfying them as soon as you can or letting them extend to the very end. Some expectations may be strong enough to last the entire length of the story, simply because they’re too big to be resolved by a single moment of exposition or action. Knowing this, it’s important to remember that you can also hide your story’s trajectory, presenting it in a subtle way. You create an expectation and then upend it.

To briefly turn to other examples, Knives Out (2019) sees an admission of guilt at the end of its first act. But this doesn’t really solve the mystery, as many loose ends still hang untied with this revelation, and while the rest of the film is focused on preventing the guilty party from getting caught, solving the mystery becomes the underlying plot thread that leads the film to its conclusion. Meanwhile, When Harry Met Sally… (1989) opens with the sense that its two lead characters are far too incompatible to ever get together. But will the viewer really take their disagreements at face value? There is a sense of satisfaction that comes with the film spanning twelve years—a long-enough time for the two main characters to possibly change their minds about one another.

In my view, the best openings make a promise to the reader: by the end of this story, this will happen. You can declare this direction to your reader, or you can whisper it in their ear. From that moment on, how you fulfill that promise, whether you choose to satisfy or subvert it, is entirely up to you.

Before we wrap up today’s post, I just wanted to take a quick break to invite further examples and even counterpoints to what we’ve discussed. Breaking away from film for a bit, I’d love to shout out Miranda July’s “The Swim Team” from her collection No One Belongs Here More Than You as a perfect example of a story that sets up a trajectory for its reader. Other examples that work for me and demonstrate this idea to varying degrees are “Brownies” by ZZ Packer and even the opening to Min Jin Lee’s novel Pachinko. What are your favorite story openings and why they resonate with you?

As I said in the introductory post, I want to end every newsletter with one or two exercises: one for reading/viewing and one for writing. These exercises are inextricably linked, so that you can see how your consumption habits either profoundly or subtly influence your writing.

This approach speaks to my own learning process, which is that I am always looking at the moments I love most in film and fiction, and asking myself, “So how do I do that?” The result, I find, is never the same as what I saw in the first place.

So, without any more ado, here are this week’s exercises:

Go back to the last interesting story you read, be it a film, a piece of short fiction, a book, or a series episode, and look specifically at how it starts and how it ends. In your writing journal or notebook, try to describe how the beginning foreshadows the ending. Does it succeed in telling you where and how the story will end? If the ending surprises you, how might you still draw a connection between that ending and the beginning? What’s changed in the world of the story between Point A and Point B?

Specificity gives rise to the starting point. Write the following sentences down, taken from Vladimir Nabokov’s story “Signs and Symbols”: “The telephone rang. It was an unusual hour for it to ring.” In thirty seconds, list as many questions as you can think of stemming from these two sentences. Got them down? Now encircle the three most interesting questions you’ve written, and spend the next five minutes answering them. Make sure to open your piece with the two sentences from our writing prompt.

Thanks for indulging my fancy for this truly gruesome film. I know horror—and especially this type of horror, which leans into gore—is not for everyone, but I’ve been thinking about its opening for months now, so it felt like a perfect example to start with. Next time, we’ll continue talking about openings, but instead of focusing on how a story could start, we’ll discuss timing and when a story should start. See you in two weeks!

Just discovered your substack here - fantastic! Will take some time to work through the exercises but wanted to drop a quick note here to say this post was super helpful to read through to understand how the lesson transfers into writing.

For the exercise #1, I chose a recent story in the New Yorker, March 6, 2023, that really haunted me after reading it: Snowy Day by Lee Chang-Dong (translated by Heinz Fenkl and Yoosup Chang from the original Korean). Working through the exercise really helped me to understand how the "promise" to the reader in the first scene could be rendered with such subtlety to foreshadow the ending...when I first read the story I was unaware of how this promise was pulling me through to to the end...studying it (and writing about it) more intentionally with this exercise really helped to learn the craft elements layered in to achieve the foreshadowing effects.

Thanks for posting!!